原文链接:https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-019-1693-2

One thousand plant transcriptomes and the phylogenomics of green plants

Abstract

Green plants (Viridiplantae) include around 450,000–500,000 species [1,2] of great diversity and have important roles in terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems. Here, as part of the One Thousand Plant Transcriptomes Initiative, we sequenced the vegetative transcriptomes of 1,124 species that span the diversity of plants in a broad sense (Archaeplastida), including green plants (Viridiplantae), glaucophytes (Glaucophyta) and red algae (Rhodophyta). Our analysis provides a robust phylogenomic framework for examining the evolution of green plants. Most inferred species relationships are well supported across multiple species tree and supermatrix analyses, but discordance among plastid and nuclear gene trees at a few important nodes highlights the complexity of plant genome evolution, including polyploidy, periods of rapid speciation, and extinction. Incomplete sorting of ancestral variation, polyploidization and massive expansions of gene families punctuate the evolutionary history of green plants. Notably, we find that large expansions of gene families preceded the origins of green plants, land plants and vascular plants, whereas whole-genome duplications are inferred to have occurred repeatedly throughout the evolution of flowering plants and ferns. The increasing availability of high-quality plant genome sequences and advances in functional genomics are enabling research on genome evolution across the green tree of life.

绿色植物(Viridiplanta)约有 45 万至 50 万不同物种,它们在陆地和水生生态系统中起着重要的作用。作为“千种植物转录组计划”的一部分,我们对泛植物界中的 1124 种物种的转录组进行了测序,包括绿色植物(Viridiplanta)、灰藻门(Glaucophyta)和红藻门(Rhodophyta)。我们的分析为研究绿色植物的进化提供了一个健壮的系统基因组框架。在大多数推测的物种关系、跨多个物种树和超级矩阵的分析中得到了很好的支持。但在质体之间和核基因树的几个重要的节点之间产生了矛盾,凸显出了植物基因组进化的复杂,其中包括多倍性、物种快速形成和灭绝。祖先变异的不完全谱系分选、多倍体化和基因家族的大规模扩张时不时打断绿色植物进化史。尤其,我们发现,尽管在开花植物和蕨类植物的进化过程中推测发生了多次的全基因组的复制,但大规模的基因家族扩张是要早于绿色植物、陆生植物和维管植物的起源。此外,测序得到越来越多的高质量植物基因组序列和功能基因组学的进步,使得研究跨越绿色生命之树的基因组进化成为可能。

Main

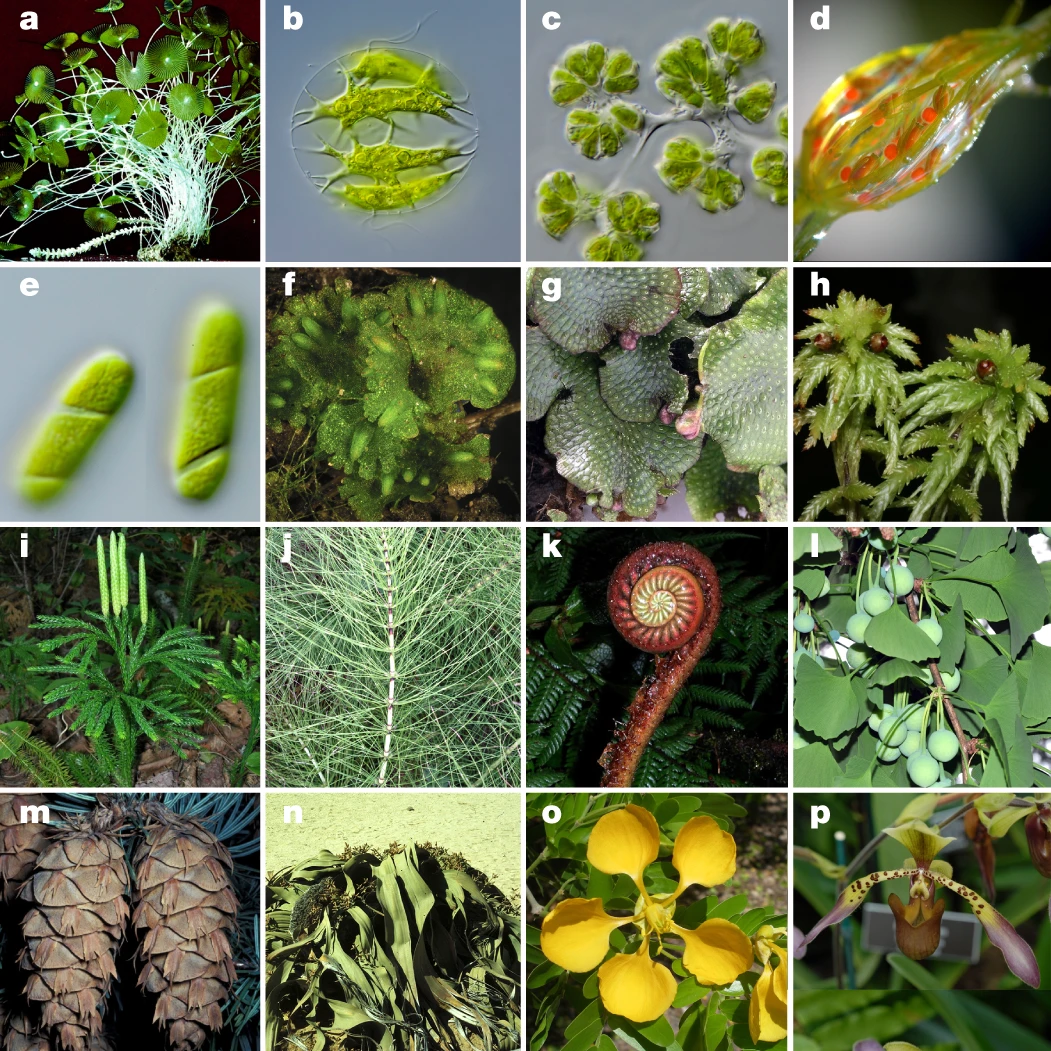

Viridiplantae comprise an estimated 450,000–500,000 species[1,2], encompass a high level of diversity and evolutionary timescales[3], and have important roles in all terrestrial and most aquatic ecosystems. This ecological diversity derives from developmental, morphological and physiological innovations that enabled the colonization and exploitation of novel and emergent habitats. These innovations include multicellularity and the development of the plant cuticle, protected embryos, stomata, vascular tissue, roots, ovules and seeds, and flowers and fruit (Fig. 1). Thus, plant evolution ultimately influenced environments globally and created a cascade of diversity in other lineages that span the tree of life. Plant diversity has also fuelled agricultural innovations and growth in the human population[4].

绿色植物约有 45 万至 50 万种,拥有丰富的多样性和长时间的进化历程,并在所有陆地和大多数水生生态系统中发挥着重要的作用。这种生态多样性源于进化,形态和生理上的改变,使得移植、扩张、发展新的栖息地成为可能。这些改变包括多细胞化,植物角质层进化,保护胚胎,气孔,维管组织,根系,胚珠,种子以及花和果实(图片 1)。因此,植物进化最终影响了全球的生态环境,并贯穿了生命之树,创造了许多不同的世系。

a–e, Green algae. a, Acetabularia sp. (Ulvophyceae). b, Stephanosphaera pluvialis (Chlorophyceae). c, Botryococcus sp. (Trebouxiophyceae). d, Chara sp. (Charophyceae). e, ‘Spirotaenia’ sp. (taxonomy under review) (Zygnematophyceae). f–p, Land plants. f, Notothylas orbicularis (Anthocerotophyta (hornwort)). g, Conocephalum conicum (Marchantiophyta (thalloid liverwort)). h, Sphagnum sp. (Bryophyta (moss)). i, Dendrolycopodium obscurum (Lycopodiophyta (club moss)). j, Equisetum telmateia (Polypodiopsida, Equisetidae (horsetail)). k, Parablechnum schiedeanum (Polypodiopsida, Polypodiidae (leptosporangiate fern)). l, Ginkgo biloba (Ginkgophyta). m, Pseudotsuga menziesii (Pinophyta (conifer)). n, Welwitschia mirabilis (Gnetophyta). o, Bulnesia arborea (Angiospermae, eudicot, rosid). p, Paphiopedilum lowii (Angiospermae, monocot, orchid). a, Photograph reproduced with permission of Thieme Verlag, Stuttgart66. b–e, Photographs courtesy of M. Melkonian. f–j, l–n, p, Photographs courtesy of D.W.S. k, Photograph courtesy of R. Moran. o, Photograph courtesy of W. Judd.

a-e,绿藻类。a,

TODO

Phylogenomic approaches are now widely used to resolve species relationships[5] as well as the evolution of genomes, gene families and gene function[6]. We used mostly vegetative transcriptomes for a broad taxonomic sampling of 1,124 species together with 31 published genomes to infer species relationships and characterize the relative timing of organismal, molecular and functional diversification across green plants.

系统基因组学方法现在被广泛用于解决物种关系、基因组的进化、基因家族和基因功能。我们利用从 1124 种植物中通过分类学的抽样,获得样品的植物转录组,并结合 31 个已发表的基因组来推断物种关系,描绘出绿色植物的有机体、分子和功能多样性的诞生的相对时间。

We evaluated gene history discordance among single-copy genes. This is expected in the face of rapid species diversification, owing to incomplete sorting of ancestral variation between speciation events7. Hybridization8, horizontal gene transfer9, gene loss following gene and genome duplications10 and estimation error can also contribute to gene-tree discordance. Nevertheless, through rigorous gene and species tree analyses, we derived robust species tree estimates (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Figs. 1–3). Gene-family expansions and genome duplications are recognized sources of variation for the evolution of gene function and biological innovations11,12. We inferred the timing of ancient genome duplications and large gene-family expansions. Our findings suggest that extensive gene-family expansions or genome duplications preceded the evolution of major innovations in the history of green plants.

我们评估了单拷贝基因之间的基因史的不一致性。这是预期在面对快速物种多样化,由于不完整的分类祖先变异之间的物种事件

Integrated analysis of genome evolution

Primary acquisition of the plastid

The history of Viridiplantae

Synthesis

Methods

Data availability

Code availability

References

- Corlett, R. T. Plant diversity in a changing world: status, trends, and conservation needs. Plant Divers. 38, 10–16 (2016).

- Lughadha, E. N. et al. Counting counts: revised estimates of numbers of accepted species of flowering plants, seed plants, vascular plants and land plants with a review of other recent estimates. Phytotaxa 272, 82–88 (2016).

- Kumar, S., Stecher, G., Suleski, M. & Hedges, S. B. TimeTree: a resource for timelines, timetrees, and divergence times. Mol. Biol. Evol. 34, 1812–1819 (2017).

- Schery, R. W. Plants for Man 2nd edn (Prentice-Hall, 1972).

.4fn9eu502dm0.jpg)